HODA AFSHAR was born in Tehran, Iran (1983), and is now based in Melbourne, Australia. She completed a Bachelor degree in Fine Art– Photography in Tehran, and her PhD thesis in Creative Arts at Curtin University. Hoda began her career as a documentary photographer in Iran in 2005, and since 2007 she has been living in Australia where she practices as a visual artist and also lectures in photography and fine art. Hoda is represented by Milani Gallery in Brisbane, Australia.

Through her art practice, Hoda explores the nature and possibilities of documentary image-making. Working across photography and moving-image, she considers the representation of gender, marginality and displacement. In her work, she employs processes that disrupt traditional image-making practices, play with the presentation of imagery, or merge aspects of conceptual, staged and documentary photography.

Hoda’s work has been widely exhibited both locally and internationally and published online and in print. Her work is also part of numerous private and public collections including the National Gallery of Victoria, UQ Art Museum, MUMA Collection, Murdoch University Art Collection, Art Gallery of Western Australia and Monash Gallery of Art. Throughout her career, Hoda has been shortlisted for many prestigious art awards, and in 2015 she won Australia’s National Photographic Portrait Prize and in 2018 won Bowness Photography Prize. She was also selected as one of the top eight young Australian artists to exhibit at Primavera 2018 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney. Hoda is a member of ‘Eleven’, a new collective of contemporary Muslim Australian artists, curators and writers whose aim is to disrupt the current politics of representation and hegemonic discourses.

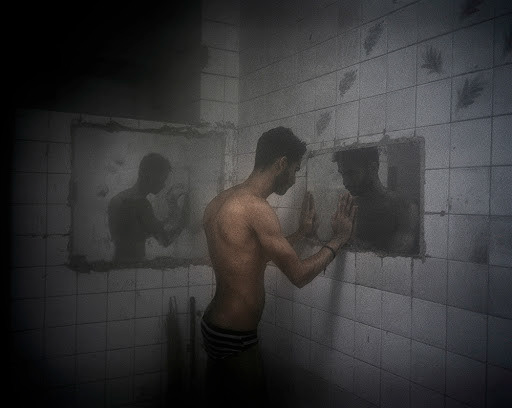

Today we had the privilege of having an artist talk from Hody Afshar which was incredibly inspirational. The 38-year-old photographer, born in Iran and migrated to Australia is now in London on a residency. She has had an extremely colourful career and her work has had exposure on a global level. She talked through her early stages of her career in Iran where she shot in a hidden documentary style to create works around the fringes of society in Iran which is never shown publicly. When she moved to Australia she struggled to create new photographic work and for almost 10 years did not shoot and share anything publically. She then signed onto a masters degree which moved into PhD study around the ideologies of identity and gender. Her 2016 project “Behold” explored young homosexual men in a bathhouse in Iran. This body of work was shot in a steam room where the homosexual men went to relax and interact with each other. This work became an exhibition and the photographs were printed largescale to hang on the exhibition walls. She went on to talk about the rest of her project that she has worked on; Speak in The Wind, Carnival, and Remain.

I was excited to see her work and hear the stories she had to tell about the journeys that she has been on. Afshar is a photographer that takes risks and isn’t afraid of making art under the noses of the authorities which is highly respectable. After listening to her retrospective talk I felt a sense of inspiration that I too could be a part of telling the lesser-known stories through my practice as a photographer.

“At first glance the video looks like a tourism promo. There is lush tropical jungle. Fat, glistening fish. White sands. Azure water. Remain, by Iranian-Australian artist Hoda Afshar, was not filmed in paradise, however, but in a prison: Manus Island.

“I wanted to [move beyond] images of a refugee behind bars,” says Afshar. “I wanted the subject to decide how to share the story: to give them autonomy and agency.”

Melbourne-based Afshar is one of eight young Australian artists whose work is now showing at the annual Primavera exhibition at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA). The 35-year-old’s often confronting photography asks us to rethink how we look at marginalised people and those on the outside.

In Behold, Afshar entered an Iranian bathhouse to shoot moody, achingly beautiful images of gay men. In Under Western Eyes, women in chadors are given the Andy Warhol treatment: posing against bright pops of colour, they smoke cigarettes, pout their lips and clutch lapdogs. In one photograph, we don’t see a face at all: just a long thick Barbie-blonde plait emerging out of the dark folds of fabric. In October, her portrait of Iranian journalist and activist Behrouz Boochani won the Bowness Photography Prize.

Afshar insists that “images share a lot of power in controlling the minds of society – for me, it’s recognising that power.”

Born in Tehran, Afshar moved to Australia in 2007 when she was in her early 20s. Her love of poetry, and her interest in politics, was instilled in her at a young age from her father, a lawyer of Kurdish background and a self-described feminist. He died five years ago but her mother remains in Tehran.

“Trump put sanctions back on Iran. The country is in crisis and is economically collapsing – people’s lives are being absolutely shattered by these policies,” she says, unable to contain her anger. “We’re talking about 80 million people: the middle class is disappearing completely. Our money has no value anymore. Wages haven’t changed but the price of everything is 10 times more.”

Slight and softly spoken, with cropped dark hair, Afshar possesses a fierce intellect, moving with ease between theories on photography to Edward Said’s seminal work, Orientalism. Said’s description of “the Other”, in particular, hit home when she moved to Australia and found herself a minority.

“I recognised pre-judgements over my identity, especially as an Iranian female migrant. … Your identity becomes a name tag that you wear every day – you have to constantly work against an image that is imposed on you,” she says, leaning forward intently.

Afshar rails against exotic tropes which depict the Middle East, either presenting the culture as titillating or confirming it as inferior, backward and oppressed. In order to address this, her work is carefully – unapologetically – staged. While others might choose candid shots to tackle similar issues, she wants to show the “limitations in storytelling and [that] nothing can fully represent truth and reality”.

“When the camera is present in the room, nothing is real anymore. As soon as you point a camera to someone, people don’t act the way they normally do,” she explains.

This matters in art: for centuries, painting and drawing – representations seen through the (literal) brush of the artist – were the only visual methods available to document people, events and histories. “And then photography comes along and we accept it like pure truth,” says Afshar. “It’s like any other art form – it’s subjective.”

Afshar’s decision to travel to Manus Island earlier this year (she entered on a tourist visa) emerged from frustration over Australia’s hypocrisy.

Australia is a “democratic country. It’s first world. It’s advanced. We care about morality, we care about humanity. All of those claims which make ‘the rest inferior to the West’ – so how can this be happening under this government? And how can we go about our lives on a daily basis ignoring this in the background?” she says.

The artist’s point of contact on Manus Island was Boochani – who, like Afshar’s father, is of Kurdish descent. “Kurdish people are famous for their strength and resistance. No matter how much pressure they are under, they still hold their heads up and they don’t give up,” says Afshar.

Channelling this, in Remain the men look directly at the camera, telling their stories. “We’ve been hidden from the world,” says one. Another discusses the desperation that has led men to swallow razor blades. Or washing powder. Or shampoo. Mostly, they talk of death – a topic that sits uneasily in the abundance of teeming life that surrounds them.

“Every single one of them talked about the death of a friend there. And every single one told me that their biggest fear is that they might die on this camp too,” says Afshar.

Many of the stories Afshar shares with me are traumatic. One Sudanese refugee she worked with wept when she took him to film on a small nearby island: it was the first time in five years he had seen the ocean. Another suddenly erupted in a red rash. His friends told her: “When we face a little bit of freedom, our souls cannot handle it.”

Important for both Afshar and Boochani was to dispel the image of refugees as a “voiceless homogenous group of miserable beings”. Even the word “refugee”, she points out, is “heavily pregnant with images that reduce the individual to stereotypes”.

Photojournalists and documentary filmmakers, she says, are “complicit in feeding this machine that continues to produce and produce mass stereotypes – that never rises above this [idea that refugee men and women] are inferior”.

Is art any better, I ask? Can it make a difference? And will watching a video in the MCA – visited largely by an educated urban elite in Sydney’s wealthy harbour setting – really make people care?

Boochani believes that art can hit a home truth where reportage fails: that while the public has “become immune to the language of journalism”, art, he tells the Guardian, is “impossible to ignore”.

Remain attempts to force us all to look. Hard. At one point in the video a man recites a poem, his voice echoing above the sound of the tropics. “Freedom,” he chants, is a “heavy gift”.”

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/nov/13/from-manus-island-to-sanctions-on-iran-the-art-and-opinions-of-hoda-afshar