“Edward Burtynsky is regarded as one of the world's most accomplished contemporary photographers. His remarkable photographic depictions of global industrial landscapes represent over 40 years of his dedication to bearing witness to the impact of humans on the planet. Burtynsky's photographs are included in the collections of over 60 major museums around the world, including the National Gallery of Canada, the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, the Tate Modern in London, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in California.

Burtynsky was born in 1955 of Ukrainian heritage in St. Catharines, Ontario. He received his BAA in Photography/ Media Studies from Ryerson University in 1982, and in 1985 founded Toronto Image Works, a darkroom rental facility, custom photo laboratory, digital imaging and new media computer-training centre catering to all levels of Toronto's art community.

Early exposure to the sites and images of the General Motors plant in his hometown helped to formulate the development of his photographic work. His imagery explores the collective impact we as a species are having on the surface of the planet; an inspection of the human systems we've imposed onto natural landscapes.” (Burtynsky,2021)

Anthropocene

“Anthropocene: The Human Epoch” is a multidisciplinary body of work between Edward Burtynsky, Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier which was completed in 2018. They embarked on a journey of visual exploration across the globe to document the spaces on our planet that have been geologically changed by mankind. A cinematic piece was made, photographs were taken and a VR Simulation was made. Travelling to twenty-one countries and six of our continents to visually narrate the harm and terrifying impact that man is having on its land. This visual enquiry is open to everyone and visually communicates the epoch that scientists are arguing that we are living in, The Anthropocene.

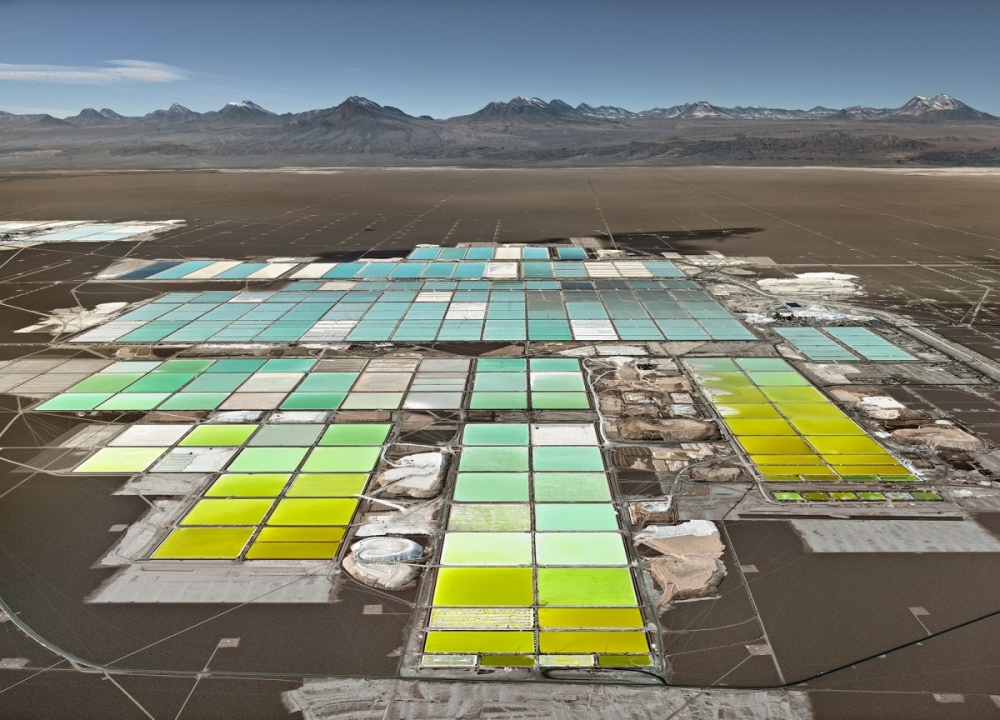

The vast beauty of Burtynsky’s photographs allows the viewer to overlook the reality of what is in front of them. An angle and perspective, almost painting-like which create an abstract distortion of that land that has been photographed. It is not until you examine the depth of the land captured that you notice the broken down forest’s, oil-stained rivers, man drive machines which all break down the global mass destruction of planet Earth.

Burtynsky’s “Anthropocene” sits next to a number of environmental documentaries that have been created in recent years. I believe it is evident in the present that we need to react to the environmental damage that humanity has placed on planet Earth. Documentaries such as “Seaspiracy'', David Attenborough’s “Life on Our Planet'', “Chasing Coral”, “Cowspiracy”, “Before The Flood” are just a fraction of cinematography that sits alongside “Anthropocene” which documents the effects of which modern-day human life has on our planet. The mass collection of these documentaries indicate a general consensus of amplified awareness that humanity needs to change the way in which they live on the Earth.

One of the criticisms of Burtynsky’s work is that the beauty of his images hinder the true terror of the landscapes that he documents. If you have stood at the bottom of a Burtynsky print then you yourself are aware of the state of awe his majestically created images render. Wainwright communicates in his Guardian article “If his message is one of impending catastrophe – or indeed a catastrophe that’s already happened – it is tempered by the fact that these man-made scars are incredibly seductive. Who could deny the alchemical allure of the toxic phosphor tailings ponds in Florida, or the beauty of the scrubby patchwork quilts left by mass deforestation? As Burtynsky admits, his images would be equally at home on a Greenpeace poster or the cover of an oil company’s annual report. “The work asks more questions than it answers,” he says. ‘Which is what artists are there to do.’ ”. Burtynsky constructs a point well considered in this conversation, perhaps it is not an artist's job to play the part of the activist but it is to visually document in order to empower the viewer’s response with their own emotional manner. In the image above we can see the huge machines that rip apart the land at the North Rhine Coal Mine in Germany. For some, this is a scene of environmental terror that is scarring our land and damaging our finite planet. However, at first, there is some beauty in the photograph with its visually alluring composition and satisfying carved out shapes which deludes the viewer into embracing the power of a human manipulated landscape. Without embracing the depth of context behind Burtynsky’s body of work, the viewer is unlikely to perceive a level of dystopian visual language as very little photographic trauma is captured and created. Thus, this can support Burtynsky's comment that it is the job of an artist to make the viewer ask more questions than to answer which denies artistic bias and allows the viewer’s interpretation to take president in the meaning behind the body of work. Burtynsky may think that they best way to draw people into what he is making comment about then the more appropriate way of going about it is by producing beautifully composed photographs that make the viewer ask more questions than they give.

Perhaps Burtynsky’s prepossessingly constructed photographs are designed for the high price that a collector would have to pay if they wanted to own one of his prints. On Collector Daily, the prices of his “Anthropocene” prints are broken down “the 48×64 diptych is $54500, and the 120×215 print is $120000” (Knoblauch, 2018). These premium prices parallel the high profile photographer who has dedicated his career to photographing human manipulated landscapes. However, it is impossible to dismiss the hypothesis that the aesthetic beauty coincides with the high prices of his photographs. As horrifying and traumatic photographs of the human destroyed world are less likely to become a desirable piece of art compared to the visually pleasing Burtynsky prints. “His omniscient viewpoint turns environmental affronts into harmless geometries, the consistent beauty of his images draining away any sense of emotion or outrage we might normally be expected to feel.” (Knoblauch, 2018). It could be argued that aesthetic beauty is created in an artistic sense in order to keep the photographer neutral from an environmental opinion. Burtynsky states during an interview with Fatema Ahmed “The Anthropocene doesn't necessarily have to end in a negative way - we both agreed at the time that we shouldn't paint this as the end of the world as we know it. It could be an epoch with a reasonable outcome if we can get our act together, or it could be a terrible one. We wanted to keep that open-endedness in all our thinking in the design of the project.” (Burtynsky, 2018). This supports the reasoning of the non-bias stance that the artist’s had when they were creating the body of work. However, it’s impossible to dismiss the fact that Burtynsky still sold his prints for a high amount of money. “Burtynsky also shows his work exclusively in art galleries and he sells them for high prices as artworks. The books about his work are mere art catalogues that do not explain much about the sites in question or the circumstances in which the photographs were taken. As Bordo states: because of Burtynsky's ambition to make his photographs artful, many of them appear to undermine what they signify. Tampering with the photographic referent in order to expose the photograph as a picture object, is an arduous enterprise full of paradox, disturbance and concern that the spectacular effect might erode the referent itself. Is the weakening of the referent's hold on the photograph the price to be paid for aesthetics? Is the cost justified?” (Gerda, 2009). Here, Gerda is talking in 2009, after the release of Burtynsky’s body of work “Manufactured Landscapes” which was shot and exhibited in a much similar way to the “Anthropocene”. The aesthetic beauty of Burtynsky’s photographs plays a neutral stance which allows the viewer to be drawn into the work without feeling like they are looking at environmental propaganda. Also adding a desirable uniform to the collector value of his photographic practice.